Conservative vector field

In vector calculus a conservative vector field is a vector field which is the gradient of a function, known in this context as a scalar potential. Conservative vector fields have the property that the line integral from one point to another is independent of the choice of path connecting the two points: it is path independent. Conversely, path independence is equivalent to the vector field being conservative. Conservative vector fields are also irrotational, meaning that (in three-dimensions) they have vanishing curl. In fact, an irrotational vector field is necessarily conservative provided that a certain condition on the geometry of the domain holds: it must be simply connected.

An irrotational vector field which is also solenoidal is called a Laplacian vector field because it is the gradient of a solution of Laplace's equation.

Contents |

Definition

A vector field  is said to be conservative if there exists a scalar field

is said to be conservative if there exists a scalar field  such that

such that

Here  denotes the gradient of

denotes the gradient of  . When the above equation holds,

. When the above equation holds,  is called a scalar potential for

is called a scalar potential for  .

.

The fundamental theorem of vector calculus states that any vector field can be expressed as the sum of a conservative vector field and a solenoidal field.

Path independence

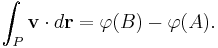

A key property of a conservative vector field is that its integral along a path depends only on the endpoints of that path, not the particular route taken. Suppose that  is a region of three-dimensional space, and that

is a region of three-dimensional space, and that  is a rectifiable path in

is a rectifiable path in  with start point

with start point  and end point

and end point  . If

. If  is a conservative vector field then the gradient theorem states that

is a conservative vector field then the gradient theorem states that

This holds as a consequence of the Chain Rule and the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

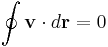

An equivalent formulation of this is to say that

for every closed loop in S. The converse is also true: if the circulation of v around every closed loop in an open set S is zero, then v is a conservative vector field.

Irrotational vector fields

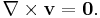

A vector field  is said to be irrotational if its curl is zero. That is, if

is said to be irrotational if its curl is zero. That is, if

For this reason, such vector fields are sometimes referred to as curl-free vector fields.

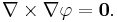

It is an identity of vector calculus that for any scalar field  :

:

Therefore every conservative vector field is also an irrotational vector field.

Provided that  is a simply-connected region, the converse of this is true: every irrotational vector field is also a conservative vector field.

is a simply-connected region, the converse of this is true: every irrotational vector field is also a conservative vector field.

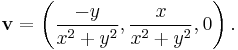

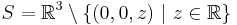

The above statement is not true if  is not simply-connected. Let

is not simply-connected. Let  be the usual 3-dimensional space, except with the

be the usual 3-dimensional space, except with the  -axis removed; that is

-axis removed; that is  . Now define a vector field by

. Now define a vector field by

Then  exists and has zero curl at every point in

exists and has zero curl at every point in  ; that is

; that is  is irrotational. However the circulation of

is irrotational. However the circulation of  around the unit circle in the

around the unit circle in the  -plane is equal to

-plane is equal to  . Therefore

. Therefore  does not have the path independence property discussed above, and is not conservative.

does not have the path independence property discussed above, and is not conservative.

In a simply-connected region an irrotational vector field has the path independence property. This can be seen by noting that in such a region an irrotational vector field is conservative, and conservative vector fields have the path independence property. The result can also be proved directly by using Stokes' theorem. In a connected region any vector field which has the path independence property must also be irrotational.

More abstractly, a conservative vector field is an exact 1-form. That is, it is a 1-form equal to the exterior derivative of some 0-form (scalar field)  . An irrotational vector field is a closed 1-form. Since d2 = 0, any exact form is closed, so any conservative vector field is irrotational. The domain is simply connected if and only if its first homology group is 0, which is equivalent to its first cohomology group being 0. The first de Rham cohomology group

. An irrotational vector field is a closed 1-form. Since d2 = 0, any exact form is closed, so any conservative vector field is irrotational. The domain is simply connected if and only if its first homology group is 0, which is equivalent to its first cohomology group being 0. The first de Rham cohomology group  is 0 if and only if all closed 1-forms are exact.

is 0 if and only if all closed 1-forms are exact.

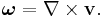

Irrotational flows

The flow velocity  of a fluid is a vector field, and the vorticity

of a fluid is a vector field, and the vorticity  of the flow can be defined by

of the flow can be defined by

A common alternative notation for vorticity is  .[1]

.[1]

If  is irrotational, with

is irrotational, with  , then the flow is said to be an irrotational flow. The vorticity of an irrotational flow is zero.[2]

, then the flow is said to be an irrotational flow. The vorticity of an irrotational flow is zero.[2]

Kelvin's circulation theorem states that a fluid that is irrotational in an inviscid flow will remain irrotational. This result can be derived from the vorticity transport equation, obtained by taking the curl of the Navier-stokes equations.

For a two-dimensional flow the vorticity acts as a measure of the local rotation of fluid elements. Note that the vorticity does not imply anything about the global behaviour of a fluid. It is possible for a fluid traveling in a straight line to have vorticity, and it is possible for a fluid which moves in a circle to be irrotational.

Conservative forces

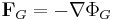

If the vector field associated to a force  is conservative then the force is said to be a conservative force.

is conservative then the force is said to be a conservative force.

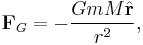

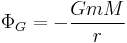

The most prominent examples of conservative forces are the force of gravity and the electric field associated to a static charge. According to Newton's law of gravitation, the gravitational force,  , acting on a mass

, acting on a mass  , due to a mass

, due to a mass  which is a distance

which is a distance  away, obeys the equation

away, obeys the equation

where  is the Gravitational Constant and

is the Gravitational Constant and  is a unit vector pointing from

is a unit vector pointing from  towards

towards  . The force of gravity is conservative because

. The force of gravity is conservative because  , where

, where

is the Gravitational potential energy.

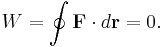

For conservative forces, path independence can be interpreted to mean that the work done in going from a point  to a point

to a point  is independent of the path chosen, and that the work W done in going around a closed loop is zero:

is independent of the path chosen, and that the work W done in going around a closed loop is zero:

The total energy of a particle moving under the influence of conservative forces is conserved, in the sense that a loss of potential energy is converted to an equal quantity of kinetic energy or vice versa.

See also

- Beltrami vector field

- Complex lamellar vector field

- Helmholtz decomposition

- Solenoidal vector field

- Longitudinal and transverse vector fields

References

- George B. Arfken and Hans J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 6th edition, Elsevier Academic Press (2005)

- D. J. Acheson, Elementary Fluid Dynamics, Oxford University Press (2005)

Notes

- ^ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, Section 7.11, Pitman Publishing Limited, London. ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- ^ Liepmann, H.W.; Roshko, A. (1993) [1957], Elements of Gas Dynamics, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0486419630, pp. 194–196.